How to avoid (some of) the worst prescription-drug ripoffs

GoodRx, carefully considering Canada, and other tools can help…sometimes

Hey there–

When it comes to picking the Worst Part of the U.S. health care system, there’s heavy competition. But prescription drugs make a strong case for themselves.

The outrageous price of insulin is the most famous example — especially because the guys who discovered it were so adamant that nobody should profit from it, they didn’t even want to patent it.

Humira’s another example. The rheumatoid arthritis drug is almost five times as expensive as when it came out in 2003. For no reason but profit.

Congress has investigated lots of similar price-gouging schemes in the past couple of years. And those are just the ones they’ve recently taken the time to investigate.

So: Nearly three in 10 people say they haven’t taken their medicine as prescribed because they can’t afford to.

But pharma companies — which make enormous profits from all this price gouging — are not the only sharks involved here.

Who are the prescription drug sharks?

The reasons our drugs are so hard to afford involve at least three sets of sharks: The pharma companies, insurance companies, and secretive middle-person companies called pharmacy benefit managers.

Each shark is trying to get every last dollar of profit from every prescription — and to avoid leaving anything for the other sharks.

Every angle any of them plays makes it more expensive for us to get medicine.

These games — the sharks fighting each other, but effectively biting us —is why I get so many emails from folks who say their insurance won’t cover their meds — unless they “try” a different, sometimes-cheaper drug … that they’ve already tried.

Or that their insurance won’t cover the specific drug they need, at all. Or any of the other unspeakably gross ways this system prevents us from getting our medication.

It’s enraging, and I don’t have a fix. But I can point you to a few tools to help.

They’re not perfect, they won’t work for everybody, and they can have downsides. The epitome of a “first-aid kit” approach.

Could this edition of First Aid Kit be useful to somebody you know? Help other people find it.

What does your insurance say you should pay? (You might have other options, but...)

When we reviewed how to pick health insurance, we talked about why it’s important to review the formulary – the document where your insurance company outlines your cost for specific drugs.

If you suddenly need a new drug, you’re gonna need to look at the formulary now.

Big picture: Lots of insurance plans use “tiers” in their formulary — making some drugs more expensive for you than others.

And sometimes those tiers reflect complete-asshole sneakiness. For instance, some formularies put all the drugs for certain chronic conditions on the most-expensive tier.

Other ways insurance plans can make drugs hard to afford include deductibles — the amount you pay before your insurance kicks in — just for drugs. Good times.

So, your doc says you should take drug X? You want to find out:

How much is drug X going to cost you, under your insurance?

Is there a comparable drug that would cost you less? (In the case of a lot of common meds, like drugs for blood pressure, there may be alternatives that do the same thing.)

Is that “comparable” drug actually just-as-good for you? It helps to have a good doc, someone you can really talk with about this question.

Having reviewed all that: Does your drug seem affordable? Great.

No? Here are a few more things to try.

Shop around: GoodRx

You may have already heard about GoodRx. If not, briefly: You can search their site for your drug, and they’ll show you what you’d pay for that drug at a bunch of different pharmacies in your area, without using your insurance — and with GoodRx discount coupons.

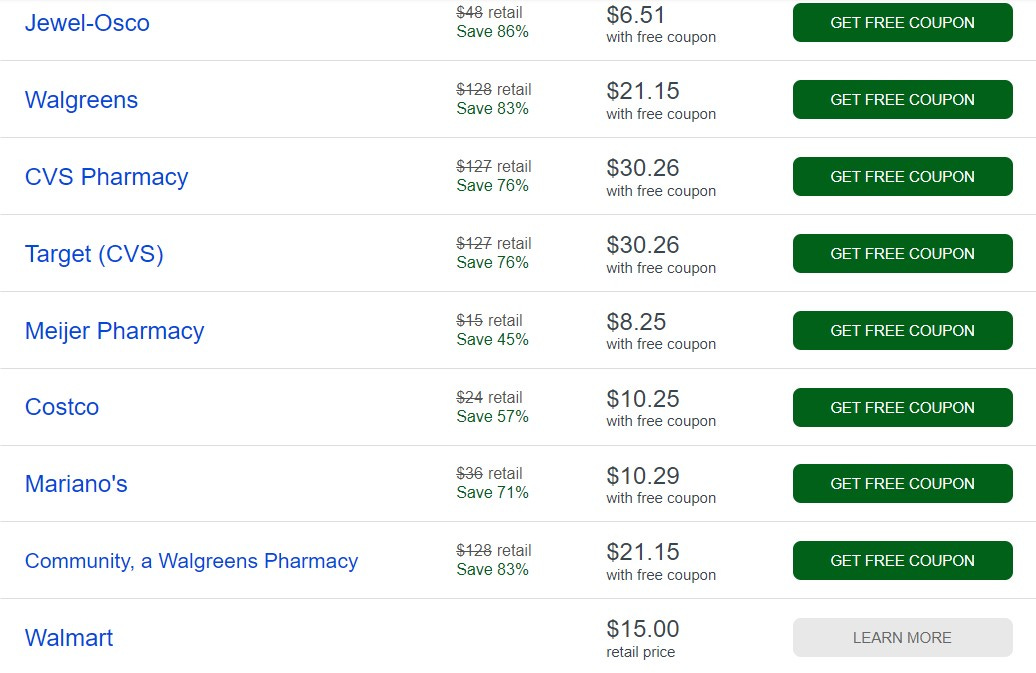

Here’s the spread, near me, for a generic version of the cholesterol drug, Lipitor. It’s wild. $6.51 to $30.26 with the coupon, up to $128 without it.

I first gave GoodRx a close look after I went to fill a prescription I’d been taking for years, and was told it would cost $720.69 for a month’s supply of an old-line, generic drug. GoodRx found me a $20 option.

That experience prompted an Arm and a Leg episode about drug pricing and the least-known of the sharks involved: pharmacy benefit managers. (You don’t need to listen, to take advantage of the tips I’m offering here, but it’s good, nerdy fun.)

Without going into those mechanics, GoodRx can save you money sometimes.

The catch with GoodRx (OK, catches)

First, for your privacy’s sake, don’t sign up for a membership if you don’t absolutely have to. Don’t tell them your name, either. They are not regulated by HIPAA, so there’s no law blocking them from selling your data — linking your name to what meds you take — which is definitely no one else’s business.

In fact, GoodRx was passing data on to companies like Facebook, until they got found out. Right now, their privacy policy says they won’t sell your data, but they could change that.

Three other things to consider:

GoodRx may not have a good-enough price on your drug. And if they have a good-enough price today, there’s no guarantee they’ll still have it later.

Any money you spend with a GoodRx discount doesn’t count against your deductible, because your insurance isn’t involved in the transaction. That could be OK for you, like if your insurance plan has a high deductible, and you’re not expecting to meet that deductible anyway (i.e., hoping not to shell out that much for health care) this year.

If you’ve got multiple prescriptions, you might need to go to multiple pharmacies to get the best GoodRx price on each one. Which you may not want to do.

And you may not want to just because you don’t have all day to run around to different pharmacies, although that is a thing.

Keeping all your prescriptions in one place means the pharmacist can look at your records and tell you if one of your meds might interact with others in a not-so-good way. Pretty important.

Yes, your doc’s office can also monitor this with you. But some of us have a hard time reaching our doc’s office or getting a straight answer from them. A pharmacist is one more potential ally in actually keeping you healthy.

So, GoodRx is a classic “first aid kit” type tool: Good to know about, and can be helpful, sometimes. But it’s more of a band-aid than a cure. Especially if you’ve got some super-expensive drugs to worry about.

One patch for super-expensive drugs: Patient assistance programs and coupons

Some drugs really do cost an arm and a leg. Hundreds of dollars a month for insulin, for example. Then there are cancer drugs and meds for rare conditions, which can run to wild amounts of money.

And with some insurance plans, you pay a lot. I’ve mentioned this before, but it’s outrageous enough to repeat: When I shopped for insurance recently, one plan I looked at had me paying 40 percent of the cost on the most expensive drugs.

Drugmakers often have “patient assistance programs” to help pay your wildly-inflated share of these unholy prices.1 Some, including insulin makers, also offer copay cards, also called coupons or discount cards.

Here are some places to check for discounts and patient assistance programs:

And: your doc’s office should have a line on resources like this, for any super-expensive drug they’re prescribing to you. (If they don’t, they should.)

There’s a catch here too, right?

Of course. We’re back to sharks.

Remember? The story behind Why Drugs Cost Us So Much involves multiple sharks, each trying to get every last dollar. And trying to avoid leaving any profit for other sharks.

These patient-assistance programs are part of that battle. They’re an effort by pharma companies to get extra money from insurance companies.

Which, gross, but worse for us: Insurance companies have responded with a shark counter-move, designed to keep us from seeing a benefit.

Let’s unpack the drug company’s shark move first:

When you have insurance, drug companies have two customers: You (paying some) and your insurance company (paying the rest).2

So, made-up example:

You need a super-expensive drug. Costs $50,000 a year.

Your insurance plan says, “Your copay is 20 percent.” That’s $10,000.

You don’t have $10,000.

Who loses? Well, you do of course. You don’t get your meds.

But the pharma company loses too. Because if you were supposed to pay $10,000, they were hoping to get the other $40,000 from the other paying customer, your insurance company.

And the pharma company doesn’t want to lose that money. That’s why they’re happy to give you the $10,000. It makes them $40,000.

Actually, this made-up example may understate how smart a shark-move “patient assistance” programs are for pharma companies.

The Wall Street Journal reported on one such program — where the drug-maker funneled the assistance through a charitable foundation — that paid back the pharma company’s investment at 20-to-1.

That is some high-level shark stuff. With some possible benefit for us.

But the insurance-company sharks have their counter-move, which wipes out that benefit.

Insurance-company Shark Counter-Move: Copay Accumulators

A few years ago, insurance companies created “copay accumulator” programs. They’re a policy where the insurance company says: “If we say you’ve got a deductible or copay or whatever, you haven’t met it until we say it’s met. And we say: It’s not met until those dollars come out of your pocket, personally.”

In other words: Any help from a patient-assistance program doesn’t count.

So, back to our made-up example:

You need a super-expensive drug. Costs $50,000 a year.

Your insurance plan says “Your copay is 20 percent.” That’s $10,000.

You get $10,000 in patient assistance.

The insurance company, with the “copay accumulator,” says: Great, that $10,000 didn’t count. You’ve still got $10,000 to pay on your deductible.

You’re back where you started, having to come up with $10,000.

Who gets that $10,000? I’d say the insurance company gets it. That’s money they’d be paying if you weren’t on the hook for it.

They saved themselves $10,000. Which came out of your pocket.

But of course they could get a lot more than that. Because if you can’t pay that $10,000, maybe you can’t get your meds at all.

Now the insurance company isn’t paying anything for those meds. They’re coming out tens of thousands of dollars ahead.

And you are not getting your meds.

I call this evil. They call it accounting.

I’m not trying to bum you out, but I want you to have a clear picture of how this stuff works. (The one touch of good news is that some states have started outlawing copay accumulators.)

And finally, I’ve got one more thing you might try.

Consider Canada (carefully)

Look, it’s technically illegal to import medicine. But as you’ve probably heard, things are a LOT cheaper in other countries, including Canada. And sometimes you can order online.

And: In general, as the L.A. Times and others have reported, you’re unlikely to get prosecuted if you’re just ordering medicine for yourself, especially if you’re getting a three-month supply or less.

But of course you want to be wary of scammers operating “online pharmacies.”

So here’s what experts tell me can work: An outfit called pharmacychecker.com allows you to shop — it’s like using Travelocity to shop for airfares, except instead of “10am flight Chicago to NYC,” you’re searching “120 doses of flovent” — and they vet sellers.

I am not telling you to break the law. I’m just saying, I might consider it.

All the usual caveats apply here:

Nothing counts against your insurance deductible

If you’re taking multiple meds, you want somebody like a pharmacist to help track of all of them, and to help look out for weird drug interactions

This is a completely unreasonable hassle, at best.

And not-at-best, there can be other, even bigger problems.

Like: Do you have a secure, climate-controlled space where packages get delivered? Could your meds go bad in transit — by getting too cold or getting too hot or getting smushed? What if your package doesn’t arrive on time, and you’re out of meds?

But this option is worth knowing about.

As usual, none of this is what we really want.

Me, I want new seasons of His Dark Materials, Babylon Berlin, and Only Murders in the Building, right away. Also, a break from alarming international news.

And I want these time-consuming, unsatisfying hacks for avoiding prescription drug ripoffs — and everything else I write about here — to become unnecessary.

But for now, I’ll take your TV recommendations, and I’ll keep going with First Aid Kit. We’ll have new Arm and a Leg episodes in March too.

Meantime, I was on Planet Money’s The Indicator recently, talking about personal bankruptcies – and how more are likely arriving soon.

More entertaining — and potentially more useful, from a guarding-your-own-health perspective — is this from the terrific Anne Helen Petersen.

I’ll be back soon with more ways for you to dodge medical ripoffs. Don’t forget to do something nice for yourself this week.

And take care of yourself.

Dan

For legal reasons, a lot of these patient assistance programs don’t come directly from the pharma companies. Congress made that illegal as part of an effort to outlaw “kickbacks” — payments from drug companies to patients, which they thought would create weird, non-medical incentives for patients to take a certain drug versus others. Like, why would I eat a carrot if you’re going to pay me to eat potato chips instead? (OK, weird analogy, but that’s the idea.) To get around this law, drug companies set up and fund “foundations” that give the money to patients instead.

FOR SUPER-NERDS: There’s a wrinkle here, which has to do with those middle-person companies, the pharmacy-benefit managers. Behind the scenes, they’ve negotiated discounts and rebates with the drug companies. So in this scenario, the drug company probably wouldn’t really get $40,000 from the insurance company. But they’d get a big chunk of money, money they don’t want to miss out on.